Incidental Exposure

Incidental or extraneous exposure to ethanol can occur from many sources, since ethanol is common in many products in our environment. Individuals being tested for EtG or EtS should be given information regarding sources of incidental exposure to avoid. Having a document that details this information can be helfpul. (download sample contract developed by Forensic Lab used in drug courts). Ethanol is used in cooking, as a solvent in over-the-counter medications, in hygiene products, antibacterial gels, perfumes, bug spray, in gasohol (ethanol added to gasoline), communion wine, is found in fermented products like wine vinegar or soy sauce, etc.. Just about every liquid product that contains sugar also contains some amount of ethanol. Additionally, the discovery that breathing vapor of ethyl alcohol in topical products can cause a positive EtG adds many additional sources of incidental exposure.

So this is where the comparison to poppy seeds ends. Unlike incidental exposure to morphine from poppy seeds (poppy seeds contain small amounts of opium), with alcohol there are literally hundreds, if not thousands, of items containing ethanol. Individuals being monitored using EtG/EtS should be warned to avoid all sources of alcohol including foods containing alcohol, alcohol-based mouthwash, otc meds containing alcohol, and vapor of any products for topical use containing alcohol. If they must use alcohol gels for hand cleaning, they should avoid the fumes by holding their hands away from the face, and using the gel in a well-ventilated area, if possible.

There is currently no known cutoff that can distinguish between incidental exposure to alcohol and beverage alcohol consumption. While it is likely true that the higher the EtG or EtS level the more likely it is that the donor or participant was drinking, a cutoff that decisively differentiates between incidental exposure and actual drinking is not known. Because more than one source of incidental exposure can occur, and because some individuals make much more EtG/EtS than others, and all the factors mentioned above can come into play, it may never be a clear line of distinction (in other words we may never have an accurate cutoff that reliably detects drinking). EtG and EtS may therefore better be thought of as indicators of likely drinking. The best approach is to confront the individual who’s had a positive test, no matter the level, with supportive encouragement to be honest and accept help early. More than half, in one series, admitted drinking. The likelihood of admitting drinking is probably related to the perceived consequences. If the individual believes they will not be harshly punished for admitting drinking they are much more likely to admit it. If the individual denies drinking further observation, evaluation, testing or treatment may be indicated.

What cutoff should be used for EtG and/or EtS? The answer is, it depends on at least two issues: 1. How much time and energy the program has to investigate lower level positives that could be from drinking but may be from incidental exposure and 2. The consequences and rigidity of programs to levy those consequences for lower values that could be from incidental exposure.

Thus, if a program has flexibility to evaluate low positives and deal with more “gray zone” cases, in which it is difficult to know what caused the positive, but wishes to detect relapses as early as possible, then a low cutoff is preferable. It is not uncommon for a low positive EtG (such as, 110ng/ml) or EtS (such as, 30ng/ml) to elicit a confession of drinking and allow earlier intervention. Some labs have reported that up to ½ of their positive EtG tests are between 100-500ng/ml. Setting a higher cutoff may cause less stress and confusion but fewer actual drinking episodes will be detected. Each program must weigh their own policies, flexibility, and desire for early detection to determine what cutoff they wish to use. Cutoffs for EtG commonly available include: 100, 250, 500, and 1,000ng/ml and EtS of approximately 1/4th these amounts (as EtS is present in urine at about 1/4 the amount of EtG).

The clinical situation with the participant should always be considered. If there have been signs or symptoms of drinking then a low positive EtG is probably more likely to truly represent proof of drinking. Nevertheless, if an individual firmly denies drinking, and it is important to “prove” whether or not the positive test was actually from drinking, programs can refer to specialized evaluation centers or individual practitioners to conduct a more thorough “addiction assessment” in which a more detailed history, interview with collateral sources of information, polygraph, testing possible sources of incidental exposure in a protected environment, can all be performed to seek to get a more definitive answer. In less critical situations, it’s often just is useful, and therapeutically more positive, to simply heighten vigilance and testing and if further drinking occurs it will likely become clear.

Other ways to monitor individuals for alcohol use include: devices (such as the SCRAM device that is worn on the ankle) that measures transdermal alcohol, administering observed Antabuse (which would then cause an anatabuse reaction if there is drinking), etc.. However, because urine testing is so common, EtG and EtS have been valuable additions to our toxicology armamentarium.

References regarding the value of using EtS as well as EtG testing. (It costs the lab about 50 cents more to test for both analytes.)

An EtG Advisory was issued by Dr. Skipper to courts and regulatory boards - August 15, 2005

The following updated advisory has been developed in response to questions from monitoring programs and regulatory boards and courts regarding EtG testing:

For the above reasons it is advisable, whenever possible, to refrain from taking action against an employee or licensee based on urine EtG testing alone. In the presence of a positive EtG test, if alcohol use is denied, I encourage the use of 1. Clinical evaluation by an addiction medicine specialist (to possibly include a polygraph if appropriate - the polygraph can often assist in a confession of use), 2. Administration of antabuse (optimally observed at 500mg daily), 3. Concomittant use of a transcutaneous alcohol sensor (such as a the TAD device available through www.bi.com), or other laboratory testing - such as Phophatidyl Ethanol) to more fully assess the meaning of a positive test. 4. Frequent (twice per day or more) breathalyzer (there is a video digital breathalyzer for home or office use). We encourage Boards, Courts, and/or Employers to rely on Addiction Medicine specialists to help interpret positive test results.

Despite the above limitation many monitoring programs have found EtG and EtS testing useful for early detection of alcohol use. These markers are far superior for detecting recent alcohol, however, more investigation needs to be performed to help use the tests more fairly and effectively.

INTERPRETING A POSITIVE EtG TEST

As far as is known to date the sole origin for the presence of EtS in urine is ethanol in vivo, and the only ways for significant ethanol to be present in the body are: 1. Drink an alcoholic beverage, 2. Consuming "incidental" alcohol (alcohol in food, normal use of hygiene products, OTC meds, etc), 3. Accidental consumption of alcohol (drinking something without knowledge that the beverage contained alcohol.) and, theoretically, 4. Produce ethanol endogenously ("auto brewery syndrome"). A positive EtG is common after #1 and #3, possible after #2, and not yet proven after #4.

The situation with regards to EtG and "incidental" exposure is similar to that of poppy seeds causing a positive morphine/codeine in urine. "Incidental" exposure for ethanol, however, is more likely because of the much higher prevalence of alcohol in many commercial products. The concept of "incidental" exposure is questionable if an agreement has been signed and the donor or participant has been carefully educated to avoid using products containing alcohol, especially for products regarding which incidental exposure is claimed.

If auto-brewery syndrome is suspected consider the following protocol. (r/o Auto-brewery protocol (pdf)).

Use of Ethylglucuronide Testing

When there is a need to monitor individuals who have agreed to remain abstinent from alcohol (such as recovering airline pilots, physicians, federal workers in safety sensitive jobs, truck drivers, etc.) who have had problems with alcohol abuse or dependence a biological marker that can accurately detect alcohol use has been needed.Until recently no satisfactory test has been available to meet these criteria. In the absence of a better marker urine alcohol has been used. Unfortunately urine alcohol testing falls short for two reasons. 1. the testing window for detection with urine alcohol is a matter of hours rather than days (poor sensitivity) and 2. fermentation, that produces alcohol, can occur "in-vitro" during shipment or storage of the sample prior to testing (poor specificity). Therefore urine alcohol testing has a significant tendency to produce unreliable results with both false negative and false positive reports.

The ideal test would need to detect alcohol use for up to several days or so (high sensitivity) and the test should only be positive following consumption of alcohol (high specificity).

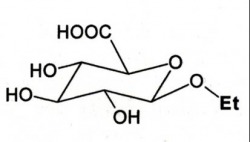

Ethylglucuronide, EtG, and ethylsufate, EtS, are new markers that are now commercially available and seem to be ideal when there is a "binary" need to know whether someone has recently been drinking alcohol or not.

An important new tool for abstinence testing in monitoring programs

(Ways EtG testing is being utilized)

So this is where the comparison to poppy seeds ends. Unlike incidental exposure to morphine from poppy seeds (poppy seeds contain small amounts of opium), with alcohol there are literally hundreds, if not thousands, of items containing ethanol. Individuals being monitored using EtG/EtS should be warned to avoid all sources of alcohol including foods containing alcohol, alcohol-based mouthwash, otc meds containing alcohol, and vapor of any products for topical use containing alcohol. If they must use alcohol gels for hand cleaning, they should avoid the fumes by holding their hands away from the face, and using the gel in a well-ventilated area, if possible.

There is currently no known cutoff that can distinguish between incidental exposure to alcohol and beverage alcohol consumption. While it is likely true that the higher the EtG or EtS level the more likely it is that the donor or participant was drinking, a cutoff that decisively differentiates between incidental exposure and actual drinking is not known. Because more than one source of incidental exposure can occur, and because some individuals make much more EtG/EtS than others, and all the factors mentioned above can come into play, it may never be a clear line of distinction (in other words we may never have an accurate cutoff that reliably detects drinking). EtG and EtS may therefore better be thought of as indicators of likely drinking. The best approach is to confront the individual who’s had a positive test, no matter the level, with supportive encouragement to be honest and accept help early. More than half, in one series, admitted drinking. The likelihood of admitting drinking is probably related to the perceived consequences. If the individual believes they will not be harshly punished for admitting drinking they are much more likely to admit it. If the individual denies drinking further observation, evaluation, testing or treatment may be indicated.

What cutoff should be used for EtG and/or EtS? The answer is, it depends on at least two issues: 1. How much time and energy the program has to investigate lower level positives that could be from drinking but may be from incidental exposure and 2. The consequences and rigidity of programs to levy those consequences for lower values that could be from incidental exposure.

Thus, if a program has flexibility to evaluate low positives and deal with more “gray zone” cases, in which it is difficult to know what caused the positive, but wishes to detect relapses as early as possible, then a low cutoff is preferable. It is not uncommon for a low positive EtG (such as, 110ng/ml) or EtS (such as, 30ng/ml) to elicit a confession of drinking and allow earlier intervention. Some labs have reported that up to ½ of their positive EtG tests are between 100-500ng/ml. Setting a higher cutoff may cause less stress and confusion but fewer actual drinking episodes will be detected. Each program must weigh their own policies, flexibility, and desire for early detection to determine what cutoff they wish to use. Cutoffs for EtG commonly available include: 100, 250, 500, and 1,000ng/ml and EtS of approximately 1/4th these amounts (as EtS is present in urine at about 1/4 the amount of EtG).

The clinical situation with the participant should always be considered. If there have been signs or symptoms of drinking then a low positive EtG is probably more likely to truly represent proof of drinking. Nevertheless, if an individual firmly denies drinking, and it is important to “prove” whether or not the positive test was actually from drinking, programs can refer to specialized evaluation centers or individual practitioners to conduct a more thorough “addiction assessment” in which a more detailed history, interview with collateral sources of information, polygraph, testing possible sources of incidental exposure in a protected environment, can all be performed to seek to get a more definitive answer. In less critical situations, it’s often just is useful, and therapeutically more positive, to simply heighten vigilance and testing and if further drinking occurs it will likely become clear.

Other ways to monitor individuals for alcohol use include: devices (such as the SCRAM device that is worn on the ankle) that measures transdermal alcohol, administering observed Antabuse (which would then cause an anatabuse reaction if there is drinking), etc.. However, because urine testing is so common, EtG and EtS have been valuable additions to our toxicology armamentarium.

References regarding the value of using EtS as well as EtG testing. (It costs the lab about 50 cents more to test for both analytes.)

- Helander A, Dahl H. Urinary tract infection: a risk factor for false-negative urinary ethyl glucuronide but not ethyl sulfate in the detection of recent alcohol consumption. Clin Chem. 2005 Sep;51(9):1728-30

- Helander A, Olsson I, Dahl H. Postcollection synthesis of ethyl glucuronide by bacteria in urine may cause false identification of alcohol consumption. Clin Chem. 2007 Oct;53(10):1855-7.

- Wurst FM, Dresen S, Allen JP, Wiesbeck G, Graf M, Weinmann W. Ethyl sulphate: a direct ethanol metabolite reflecting recent alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2006 Feb;101(2):204-11

An EtG Advisory was issued by Dr. Skipper to courts and regulatory boards - August 15, 2005

The following updated advisory has been developed in response to questions from monitoring programs and regulatory boards and courts regarding EtG testing:

- No laboratory test is 100% accurate. Clinical correlation is always important.

- Some people produce more EtG for a given dose of ethanol than others associated with a known genetic polymorphism in the human UDP-glucuronyl transferase enzyme system. The exact limits of this variation are not known.

- A positive EtG is not proof of intentional alcoholic beverage consumption. Low level positive tests are known to occur due to incidental exposure. The cutoff for possible incidental exposure vs intentional use has not been accurately established, due to many factors including; amount of "incidental" exposure, individual metabolism, hydration, kidney function, etc..

For the above reasons it is advisable, whenever possible, to refrain from taking action against an employee or licensee based on urine EtG testing alone. In the presence of a positive EtG test, if alcohol use is denied, I encourage the use of 1. Clinical evaluation by an addiction medicine specialist (to possibly include a polygraph if appropriate - the polygraph can often assist in a confession of use), 2. Administration of antabuse (optimally observed at 500mg daily), 3. Concomittant use of a transcutaneous alcohol sensor (such as a the TAD device available through www.bi.com), or other laboratory testing - such as Phophatidyl Ethanol) to more fully assess the meaning of a positive test. 4. Frequent (twice per day or more) breathalyzer (there is a video digital breathalyzer for home or office use). We encourage Boards, Courts, and/or Employers to rely on Addiction Medicine specialists to help interpret positive test results.

Despite the above limitation many monitoring programs have found EtG and EtS testing useful for early detection of alcohol use. These markers are far superior for detecting recent alcohol, however, more investigation needs to be performed to help use the tests more fairly and effectively.

INTERPRETING A POSITIVE EtG TEST

As far as is known to date the sole origin for the presence of EtS in urine is ethanol in vivo, and the only ways for significant ethanol to be present in the body are: 1. Drink an alcoholic beverage, 2. Consuming "incidental" alcohol (alcohol in food, normal use of hygiene products, OTC meds, etc), 3. Accidental consumption of alcohol (drinking something without knowledge that the beverage contained alcohol.) and, theoretically, 4. Produce ethanol endogenously ("auto brewery syndrome"). A positive EtG is common after #1 and #3, possible after #2, and not yet proven after #4.

The situation with regards to EtG and "incidental" exposure is similar to that of poppy seeds causing a positive morphine/codeine in urine. "Incidental" exposure for ethanol, however, is more likely because of the much higher prevalence of alcohol in many commercial products. The concept of "incidental" exposure is questionable if an agreement has been signed and the donor or participant has been carefully educated to avoid using products containing alcohol, especially for products regarding which incidental exposure is claimed.

If auto-brewery syndrome is suspected consider the following protocol. (r/o Auto-brewery protocol (pdf)).

Use of Ethylglucuronide Testing

When there is a need to monitor individuals who have agreed to remain abstinent from alcohol (such as recovering airline pilots, physicians, federal workers in safety sensitive jobs, truck drivers, etc.) who have had problems with alcohol abuse or dependence a biological marker that can accurately detect alcohol use has been needed.Until recently no satisfactory test has been available to meet these criteria. In the absence of a better marker urine alcohol has been used. Unfortunately urine alcohol testing falls short for two reasons. 1. the testing window for detection with urine alcohol is a matter of hours rather than days (poor sensitivity) and 2. fermentation, that produces alcohol, can occur "in-vitro" during shipment or storage of the sample prior to testing (poor specificity). Therefore urine alcohol testing has a significant tendency to produce unreliable results with both false negative and false positive reports.

The ideal test would need to detect alcohol use for up to several days or so (high sensitivity) and the test should only be positive following consumption of alcohol (high specificity).

Ethylglucuronide, EtG, and ethylsufate, EtS, are new markers that are now commercially available and seem to be ideal when there is a "binary" need to know whether someone has recently been drinking alcohol or not.

An important new tool for abstinence testing in monitoring programs

(Ways EtG testing is being utilized)

- Routine inclusion in some or all of sample testing for individuals in monitoring

- "For cause" testing (reports of possible drinking, AOB, etc)

- To analyze "dilute urine" specimens (in someone who might use alcohol and is trying to "beat the test")

- Random testing in high risk individuals (following multiple relapses, etc)

- To verify positive urine alcohol (EtS would not be present in urine that has fermented alcohol. EtG has been shown, under certain conditions to metabolize fermented alcohol into EtG if certain bacteria are present)

- Direct metabolites of alcohol (account for a very small, but important, percentage of alcohol metabolism)

- Stable compounds detectable in the urine, blood, hair and post-mortem tissue for days

- More definitive, regarding actual use of alcohol, than indirect measures (i.e. MCV, CDT, GGT, etc).

- Superior to urine alcohol because they are detectable in the urine longer and therefore have a longer time spectrum of detection (2-5 days)

- To test whether or not alcohol has been recently consumed (only useful in testing individuals who should not be drinking at all) - Thse are not tests for impairment.

- There is essentially no EtS present in the urine unless alcohol has been present in vivo. An important issue that must be considered when interpreting these tests is the possibility of incidental exposure. There are many sources of non-beverage alcohol in our environment (alcohol as a solvent (in OTC meds), in foods (i.e. vanilla extract), use in rituals (communion wine), etc.) Se FAQ for discussion of cutoffs.

- LC/MS/MS (liquid chromatography/ tandem mass spectroscopy) is currently used to detect EtG and ETS and is highly accurate. It should cost very little to test for EtS in addition to EtG. It is best to obtain both routinely if possible.

- EtG and ETS testing are proving to be particularly useful in numerous settings associated with monitoring individuals committed to abstinence: 1. professionals (such as physicians, pilots, nurses, attorneys, etc) who have had problems with alcohol abuse and have been allowed to return to work based on an abstinence agreement, 2. methadone clinics, 3. individuals with hepatitis C, 4. in legal settings (custody, etc). and 5. in school testing programs, and 6. to confirm other testing methods (i.e. transcutaneous alcohol sensors - SCRAM device)